Orchestration of Identity: Turning Algorithms into a Well-tuned Arrangement

- Gandhinath Swaminathan

- Jan 26

- 8 min read

We have spent the last eight articles building a heavy arsenal of matching algorithms. We looked at the foundational techniques of Entity Resolution (ER):

We moved from the rigid precision of Exact Matching to the nuance of Semantic Search using HNSW.

We tore apart BM25 for lexical search and combined worlds with Reciprocal Rank Fusion (RRF).

We pushed the boundaries with SPLADE and Graph Attention Networks (HGT).

We even revisited Probabilistic Record Linkage (PRL) to quantify uncertainty.

That's a lot of capability. However, a stack of algorithms isn't a strategy.

Knowing how to execute a complex vector search or a precise exact match doesn't mean you know when to apply them. A production system isn't just about running calculations. It's a coordinated sequence of decisions—knowing when to amplify the signal, when to filter out the noise, and when to halt the process—all calibrated to the specific quality of the data.

In isolation, these algorithms are just math operations. They calculate similarity scores. They don't solve business problems until you sequence them into a coherent strategy. This is where we move from individual components to a well-tuned arrangement.

The contextual understanding of a "well-tuned arrangement" in Entity Resolution is a specific orchestration of blocking, candidate generation, scoring, and classification tailored to a domain's unique constraints.

The arrangement for matching patient records in a hospital is fundamentally different from harmonizing product SKUs in a grocery chain. One demands safety; the other demands scale.

The Cost of Being Wrong

Before you pick an algorithm, you have to decide what failure looks like.

Why? Because the cost of “wrong” varies wildly by domain.

Let us explore a few examples:

In Marketing: A false positive (incorrectly merging two customers) might send duplicate emails. Annoying, but recoverable.

In Healthcare: A false positive merges Patient A's allergy to penicillin with Patient B's treatment plan. That's a lawsuit, not an annoyance.

In KYC Compliance: A false negative (missing that two accounts belong to the same person) can mean you fail to detect money laundering. The regulators don't care that your F1 score was 0.92 on a benchmark dataset.

In every ER project, you trade off Precision (avoiding false positives) against Recall (avoiding false negatives). You cannot maximize both simultaneously.

The arrangement starts by defining which error you can tolerate. Situation matters. The orchestration has to match the risk profile.

Examples of Fine-tuning Entity Resolution for Real-World Contexts

Healthcare & Patient Matching (The “Do No Harm” Approach)

Healthcare organizations run into fragmented identity at scale. A single patient might have records at their primary care physician, a specialist, a lab, a pharmacy, and an emergency room. Each system uses different identifiers. Sometimes the NHS number is missing. Sometimes the patient moved and the address changed. Sometimes their last name changed.

The Orchestration

Blocking: Extremely conservative. Block only on hard identifiers like SSN (last 4), DOB, or exact phonetic codes of surnames.

Matching Layer: This is the stronghold of Probabilistic Record Linkage (PRL) and Exact Matching. You rely on specific field comparisons—Date of Birth must match exactly; Address must be within a tight edit distance.

The Role of AI: You rarely use HNSW or Semantic Search here for the final decision because “close enough” isn't acceptable for medical history. However, you might use SPLADE to normalize messy address data before it hits the deterministic matcher.

Review: High human-in-the-loop involvement. Any ambiguity goes to a data steward.

While healthcare demands surgical precision to avoid patient safety risks, financial institutions face a different challenge: criminals actively obscuring their identities across complex ownership networks.

KYC and Anti-Money Laundering (The “Wide Net” Approach)

Financial institutions face a different challenge. A single person might have multiple accounts. A shell company might have five subsidiaries. A money laundering network might involve dozens of entities with complex ownership chains.

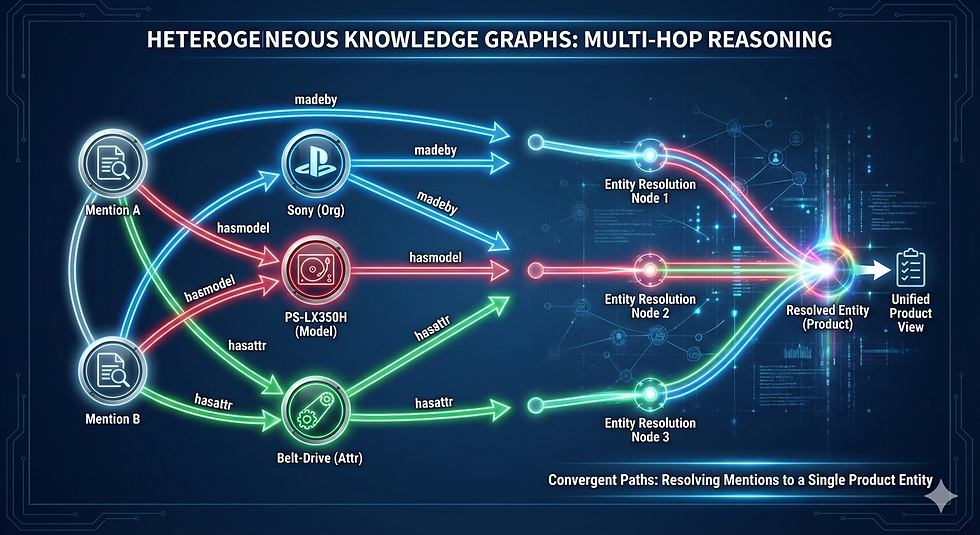

You can't solve this with pairwise matching. The signal lives in the graph structure. If Person A is an authorized signatory for Company B, which owns Subsidiary C, which has Account D, you need to traverse that chain to detect beneficial ownership.

The Orchestration

Blocking: Wide and loose. You don't trust the data entry. A name might be “Robert Mugabe” or “Bob Mugabee.”

Matching Layer: This is where Semantic Search and Phonetic Algorithms shine. You need vector embeddings (HNSW) to capture name variations and transliteration errors that exact spelling misses.

The Advanced Layer: Bad actors hide in networks. This is the prime use case for Heterogeneous Graph Transformers (HGT). You aren't just matching names; you are matching relationships. Does this entity share a phone number, an IP address, or a corporate officer with a known bad entity?

Review: High volume of manual review, but the cost of the review is lower than the cost of a regulatory fine.

In contrast to adversarial scenarios like AML, consumer packaged goods companies face a more benign problem: not entities hiding, but legitimate products described inconsistently across data feeds.

CPG Product Harmonization (The “Attribute” Approach)

Consumer packaged goods companies buy data from Nielsen, Circana, and SPINS. They also get direct feeds from retailers—Kroger, Costco, Walmart, Target. Each source describes the same physical product differently.

Nielsen calls it: “Coca-Cola Zero Sugar 12oz Can 12-Pack”

Circana calls it: “Coke Zero 12 Pack Cans”

Kroger's portal calls it: “Coca Cola Zero Sugar Soda Pop, 12 Fl Oz, 12 Count”

Same product. Three digital identities. Your demand planning system thinks these are three different SKUs and misallocates inventory.

The Orchestration

Blocking: Brand and Category driven. Before you match anything, build a product taxonomy with your domain experts.

Matching Layer: Hybrid Search is the MVP here. Use regex and domain rules to extract structured attributes. You need the lexical precision of BM25 (or SPLADE) to catch the specific token “12pk” vs “6pk,” combined with vectors to understand that “Diet Coke” and “Coca-Cola Light” are the same beverage.

The “Learned” Component: Generic embeddings (like OpenAI's text-embedding-3) are often too broad for SKUs. You often need to fine-tune the model or use Reciprocal Rank Fusion (RRF) to weight the exact keyword matches (like UPCs or MPNs) higher than the description text.

Review: Moderate human-in-the-loop involvement. Data stewards verify matches for high-value SKUs (new product launches, top sellers) and edge cases where brand names vary significantly (international products, private label).

The Framework to Build Coherent Entity Resolution

Step 1: Assess the Current State

Measure your fragmentation rate. Identify your data sources. Understand your identifiers.

Is it OCR errors? Then you need character-level n-grams or vector search.

Is it human entry typos? Phonetic algorithms work well.

Is it distinct codes (UPC, EIN)? Use exact matching.

If you don't know why your data doesn't match, you can't build the right arrangement.

Step 2: Quantify the Cost of Wrong

What does a false positive cost? If you merge two different customers and send them each other's invoices, that's a support ticket and a trust issue. If you merge two different patients and prescribe the wrong medication, that's a malpractice suit.

What does a false negative cost? If you fail to link two accounts during fraud detection, you miss the pattern. If you fail to link two product records in inventory planning, you overstock one and run out of the other.

This determines your thresholds.

Step 3: Design Your Blocking Strategy

Comparing every record to every other record (O(n^2) complexity) is impossible at scale. You need a blocking key to limit the search space.

Choose blocking keys that:

Have high cardinality (not gender).

Appear in >90% of records.

Capture domain semantics (brand for products, geography for customers).

Are relatively stable (not phone numbers that change frequently).

Common blocking keys:

Products: Brand + Category

Customers: ZIP code + first initial

Healthcare: ZIP + birth year

Financial: Last 4 of SSN + surname

Advanced: Use HNSW as a “blocking” mechanism. Retrieve the top 100 nearest vectors, then apply a heavy re-ranking model (like a Cross-Encoder or SPLADE) to those 100 only.

Step 4: Layer the Algorithms

Rarely does one algorithm do it all. The most robust systems use a waterfall approach:

Pass 1 (Cheap & Fast): Exact Match on unique IDs (Email, Phone, UPC). If it matches, stop

Pass 2 (The Search): For remaining records, run Hybrid Search (BM25 + Vectors)

Pass 3 (The Context): If ambiguity remains, check the Graph. Do neighbors align?

Pass 4 (The Steward): If the confidence score is between 0.6 and 0.8, send to a human

The Stewardship Bottleneck (and the emerging solution)

Entity resolution at scale hits a staffing problem. Industry benchmarks suggest one data steward for every 10,000 records. If you're matching 500,000 customer records across five systems, that's 50 full-time stewards just to maintain data quality. The bottleneck isn't the matching algorithms—it's the manual review queue.

An emerging trend addresses this: Agentic AI with reinforcement learning for “last-mile stewardship.” Emerging tools and specialized platforms deploy AI agents that handle routine duplicate detection and validation, escalating only ambiguous cases to human stewards. When a steward approves or rejects an agent's merge decision, that feedback becomes a training signal. The agent adapts—learning which patterns need human review and which don't.

Step 5: Set Decision Boundaries

Most entity resolution systems have three decision zones, not two:

Auto-merge: High confidence, no human review needed

Review queue: Medium confidence, flag for manual review

Auto-reject: Low confidence, keep separate

Determine these thresholds empirically using a labeled validation set and ROC curve analysis. Start with conservative thresholds (0.90 auto-merge, 0.70-0.90 review) and tune based on your cost function from Step 2. For example, if false positives cost 10x more than false negatives, shift the auto-merge threshold higher (0.95+) to reduce erroneous merges.

Step 6: Build Golden Record Logic

When you merge records, you create a “golden record”—the single authoritative version of that entity.

Decide the rules:

Which source is authoritative for each field?

Do you take the most recent value? The most complete value?

How do you handle conflicts? (Record A says the customer lives in Seattle, Record B says Portland)

Document these rules. They become your merge specification.

Step 7: Monitor and Iterate

Entity resolution isn't a one-time project. Data drifts. New sources get added. The distribution of your records changes.

Quick Monitoring Checklist:

Track precision/recall metrics weekly on held-out test set

Monitor blocking exclusion rate (target: <5% of true matches excluded)

Set up alerts for distribution shifts in similarity scores

Log false positive/negative examples for quarterly model retraining

Track steward review queue depth (target: <10% of total pairs)

Did the blocking strategy exclude the true match? Did vocabulary mismatch fool the similarity function? Feed those insights back into the arrangement. Maybe you need a new blocking key. Maybe you need to boost the weight on UPC fields. Maybe you need to add a custom NER model to catch product codes your regex missed.

What Comes Next: Why Benchmarking Can't Be Skipped

Every arrangement makes tradeoffs.

Higher precision often means lower recall.

Faster matching often means less accuracy.

Cheaper techniques often miss edge cases that expensive techniques catch.

How do you know if your well-tuned arrangement is working? You measure it.

Not with gut feel. Not with anecdotal examples. With rigorous benchmarking on labeled data.

In the final post of this series, we will cover Benchmarking. We will discuss how to build a Golden Set when you don't have one, how to calculate Pairwise F1 scores without manual review of a million rows, and how to prove to the business that your Entity Resolution system is actually solving the problem.

Series: Entity Resolution

Post 2: From exact match to HNSW

Post 3: BM25 Still Wins

Post 4: Hybrid Search and RRF

Post 5: Stop Mixing Scores. Use SPLADE

Post 6: Attention Filters SPLADE

Post 7: Heterogeneous Graph Matching

Post 8: Probabilistic Entity Resolution

Post 9: Orchestration of Identity: Turning Algorithms into a Well-tuned Arrangement (this post)

Comments